I Want to Die but I Also Want to Eat Tteokppoki, a Book That Targets Young Readers of Japan

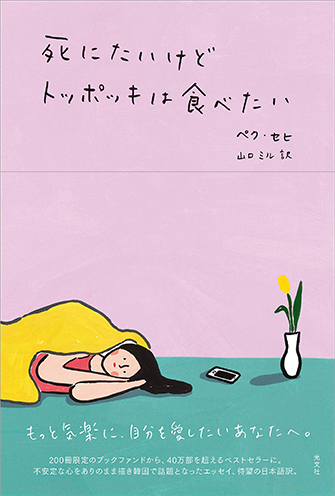

Book Covers of the Japanese Translations of I Want to Die but I Also Want to Eat Tteokppokki 1, 2

The first time I saw I Want to Die but I Also Want to Eat Tteokppokki (HEUN) was in a bookstore on my trip to Seoul in 2018. I stopped in front of the book display shelf without even realizing it, mesmerized by the soft and cozy illustrations and beautiful colors of the cover.

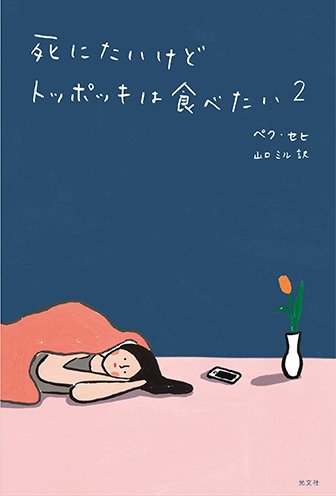

That same year in December, the Japanese translation of KIM JI YOUNG BORN 1982 (Minumsa Publishing) attracted public attention at the entrances of many bookstores in Japan. Many works of Korean literature have been translated and published over the years. After The Vegetarian (Changbi) by Han Kang received the Man Booker International Prize in 2016, there has been a wider range of works of Korean literature stocked in bookstores. However, what has really attracted the attention of readers since 2018 are works of literature or non-fiction targeting “light readers” (those who have a slight interest in book charts and Korean books), with KIM JI YOUNG BORN 1982 being in the lead. In particular, teenagers of the younger generation have shown a rising interest in cultural aspects of Korea such as K-POP, make-up, fashion, interior, and food which has also led to the rise in interest in Korean literature. I Want to Die but I Also Want to Eat Tteokppokki is a book that had the initial intention of targeting young readers, mostly consisting of Millenials.

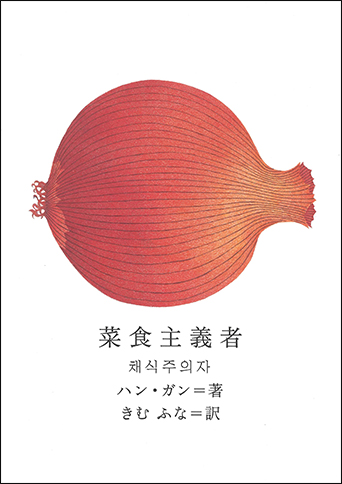

Book covers for the Japanese translations of KIM JI YOUNG BORN 1982, The Vegetarian

As mentioned at the beginning of the article, these books can be purchased as products of display “not read but stocked” as part of an interior design since their stylish cover designs attract consumers of the generation that uses social network systems centered on visuals such as Instagram or TikTok. That’s why the covers of the translated versions were designed nearly the same as the originals. The only additional touch to add some nuance was the font style of the title, which was changed to a handwritten version to make it look softer.

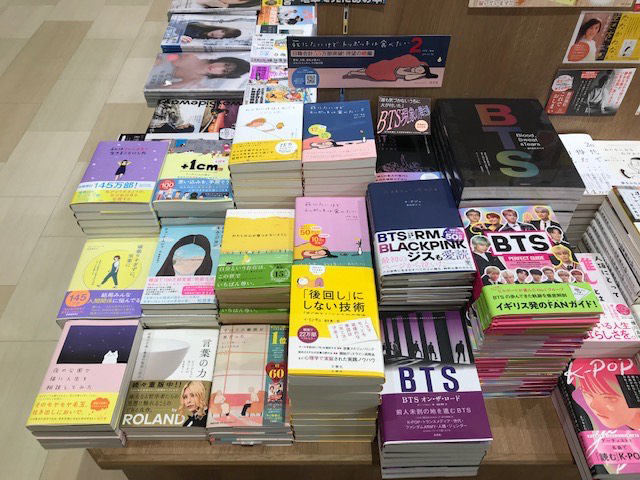

In January of 2020, 10,000 initial copies were first published, and the second batch of copies was issued in just a single week due to the increase in sales mostly centered around Amazon Japan. Within ten days of being published, 30,000 copies were sold. As intended, the number of purchasers in their teens and twenties increased significantly, drawing attention mainly on social networks. One factor of this increase might have had to do something with the increasing number of fans who became obsessed with every single bit of idol members as K-POP gained great popularity in Japan. Fans reading the books and posting reviews of books on the SNS of popular idol members has become a trend. Many reviews were posted mostly by the fans of idols, including BTS members as I Want to Die but I Also Want to Eat Tteokppokki appeared on the SNS of those idol members.

Since then, sales have increased, and an additional 40,000 copies were printed in 2020, just in time for summer vacation at schools. The additional copies planned were not enough to meet the demand, so another 10,000 copies were printed. The age group expanded into an older age group from teenagers, and sales in local bookstores also increased following the sales increase in central cities. In 2021, there were a total of 140,000 copies printed and sold. The sequel, I Want to Die but I Also Want to Eat Tteokppokki 2, has sold 60,000 copies. The two books were a hit as they sold a total of 200,000 copies altogether.

The question is, how did this book attract the minds of the younger generation? I plan on listing the reasons one after the other.

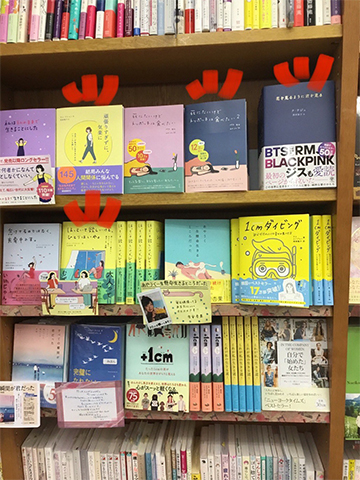

Ⓒ Kikuyashoten Matsudoten

Ⓒ KINOKUNIYA COMPANY LTD. shinjuku honten

This book is a record of the experience the writer has when encountering the unstable inner mind and the struggles faced while accepting the unstable state of mind. A characteristic of this book is that the beginning of each piece of writing starts out as a dialogue. There are many non-fiction works in Japan that portray a character overcoming depression, but in this book, the troubled mind is prescribed as a “dysthymic disorder (slight depression),” but does not fall under a single category of diseases, is recorded in detail. The book does not provide a clear ending as the writer’s mental state bounces around from the beginning to the end, although it foreshadows a bright ending. The part which makes this book interesting might be the acceptance of the uncertainty of “not being resolved.” When readers read a book that reflects what’s similar to their mental state of being unstable, some readers might realize that they are trapped in their own obsession of having to “resolve it no matter what,” “be healthy,” “move forward” as they get closer to the ending.

The theme of the book that perceives the unstable mental state is portrayed well in the title. The two contrasting desires of “wanting to die” and “wanting to eat tteokppoki” are displayed. The contrast between the seriousness of the problem in the former and the lightness or greed revealed in the latter has a subtle effect that highlights the author’s unstable psychological state, which cannot be expressed in words. The book highlights the desire for a stable conclusion without being able to relieve the unstable contrast of emotions. The author did a splendid job of portraying this kind of mental state.

This book is more than just an essay as it is similar to the text website in the form of a journal that was popular from the late 1990s to the early 2000s on the internet in Japan. The websites that attracted readers with journals and sensible poems as their main content were followed by the “SNS literature” of Instagram, Twitter, note (Japan’s SNS platform), but it seems there’s a common factor seen in this book as well since most readers are teenagers or the young generation in their twenties that know how to handle SNS well. So, for example, the main content that reads like a journal and the prose at the end of the book have common factors.

Although the type of oppression differs in Japan and Korea, minorities of society, including young people and women, do face oppression. Suppose literature has the power of fighting against oppression by speaking up in resistance. In that case, this book has the power of making readers examine their own mental states and come to realizations by empathizing with the mental state of those who send an SOS in circumstances where they get weary and hurt from oppression.

Written by Ms. Amiko Kitagawa of Kobunnsha (株式会社光文社ノンフィクション編集部 北川編子)

Translated from Japanese to Korean by Oh Kyoung-Soon (Adjunct Professor of Japanese Language & Culture at Catholic University of Korea)