Status of Korean feminism and changes made in the Korean publishing industry since 2015

There is no such thing as “Korean Feminism.” Yet, there is a history of Korean feminism fighting against the deep-seated hatred against women in society. The year 2015 is likely to be recorded as the most important period in the Korean history of feminism. In January, a Korean teenage boy who sought to join the Islamic State in Syria lamented that men are being discriminated against, voicing his hatred of women. In February, a pop culture journalist, male, published a column titled “Anencephalous feminism is more dangerous than ISIS” in a fashion magazine. This triggered women’s joint criticism of his comment and subsequently initiated feminist activism via the (hashtag) #iamafeminist on Twitter in South Korea. Later that year, a Korean rapper released a controversial song about his hate against women, and a comedian spoke out against women in a podcast. A Korean edition of a popular men’s magazine also generated a lot of debate after it featured a picture reminiscent of a woman being kidnapped. As the critiques widely spread, the magazine made a belated official apology. These only constitute the most controversial cases in the country about the issue in 2015 alone. Women preferred to call this social phenomenon “misogyny” rather than “sexism.”

On May 17, 2016, a young woman was brutally murdered at a public toilet of a karaoke bar near a subway station in Gangnam, a trendy Seoul neighborhood, at night (commonly referred to as the “Gangnam murder case”). Women defined it not as a mere reckless homicide but as a “crime of misogyny.” Angry women took to the streets to fight against the deeply rooted patriarchy and hatred against women in Korean society. Sohn Hee-Jung, a culture critic, defines the recent feminist rally that has gathered popularity among young Korean women as a “feminism reboot.” Sohn, a feminist and a doctor in film studies, borrowed the term “reboot” (meaning a whole new version of the world) to describe the 2015 feminist movement. She went further to publish <Feminism Reboot in 2015: Voices that Penetrated the Era of Hatred (Woodpencil Books, 2017)>.

-Women preferred to call this social phenomenon “misogyny” rather than “sexism”.

Korean Feminist Writers

Since 2015, Korean feminist scholars and authors have been writing about the history of misogyny and feminism – <What Happened with Misogyny?: the World of Naked Horses (Hyunsil Book, 2015)> was published, followed by many others in January 2017 such as <Feminist Moment (Greenbee Books)>, and <History of Korean Online Feminism (Woodpencil Books)>, <Megalian Uprising (Baume à l’âme)>. Though slightly different, they all intend to shed light on the formation of misogyny and how feminism has developed in Korean society.

<Feminist Moment>, <Selfish Sex: Their Sex is Wrong>, <The Challenge of Feminists>

<Selfish Sex: Their Sex Is Wrong (Dongnyok, 2015)> by Eun Ha-Sun was released in August 2015 and sold 5,000 copies in only a year despite the recession in the Korean publishing market. The book made the case that women should break away from sex life centered on masculinity and men’s desires and have “selfish sex.” It means women should also be able to talk about and pursue individual sexual desires as they are. The novel <Egalia’s Daughters (original title: Egalias døtre, Golden Bough, 1996)> also gained popularity – 20 years after its first print, 4,000 copies were sold in Korea in just two months from November to December 2015. Gerd Brantenberg, the author of this book, depicts a world in which the traditional sexual hierarchy and gender roles are completely reversed. Since it was first introduced in Korea in 1996, it received such great love from readers in almost 20 years. Along with this book, the revised edition of <The Challenge of Feminists (Gyo-yang-in, 2005)> by Jeong Hee-jin, a prominent women’s studies scholar and writer of the book, has again become popular since its first print in 2005. It is the most recognized and critical Korean feminist book. The author explains that feminism is her epistemology of looking at the world, and is the most “realistic” view of the world. She touches upon domestic violence, love and sex, social “expectations” for victims, gender roles, male sexuality and militarism, “female prostitutes” and feminists, and other heated agenda of feminism.

<We Need a Language: 1st Step for Feminism>, <Escaping the Corset>

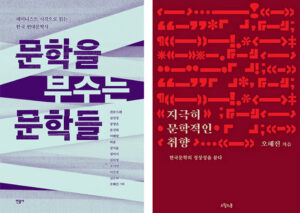

Lee Min-Kyung’s <We Need a Language: 1st Step for Feminism (Baume à l’âme)>, published in July 2016, sold nearly 10,000 copies in a month. This book claims itself to be a “Conversational Manual for Sexist Topics” that women can refer to when they are expected to provide logical reasons for the damage inflicted by gender discrimination, sexual violence, or other hierarchical misdeeds. The “Gangnam murder case” infuriated the author and motivated her to finish writing the book in nine days after the incident and establish a publishing company with her feminist friends. She has now become a well-known feminist writer in Korea. Her book takes a stand against rigid beauty ideals and unlaces the metaphorical corset. Several media outlets listed it as the Book of the Year, which attests that “Escaping the Corset” is a highly symbolic and significant concept of Korean feminism. was released in Japan in December 2018 under the title <私たちにはことばが必要だ: フェミニストは黙らない (We Need a Language: Feminists should not be silent)>.

<Kim Ji Young, Born 1982>, a sensation that has got the whole world taking.

The most important event in the Korean feminist publishing industry is certainly the novel . The first edition of this novel, written by Cho Nam-Joo, was published in Korea in October 2016. It became a huge bestseller again in three years, with the release of a film based on the novel. It tells the life story of a young ordinary Korean woman born at the end of the twentieth century, focusing on her experience as a full-time housewife after marriage. By raising questions about endemic irregularities, institutional oppression, gender inequality, and marginalization in the patriarchal society that constantly hold her back, the book depicts the character in a way that resonates with the readers. In the novel are words that demonstrate the online hate discourse against women in Korea such as doenjang (Korean traditional soybean paste) girl which refers to a young woman who likes luxury items and Mom-choong (choong means a bug in Korean) which describes a mother who only cares for her children with no respect for others. There are scenes in the book where the main character Kim Ji-Young is also criticized or laughed at for being a doenjang girl and Mom-choong. These aspects of the novel strongly resonated with women of the same generation.

The copyright of the novel was sold to 19 countries, including China, Japan, the U.K., Germany, and France. That of the film was also sold to 37 countries. Most notably in China, <Kim Ji Young, Born 1982> became one of the best-selling new novels in online bookstores after one month upon its release in September 2019. It gained so much popularity that as of early February 2020; the number of copies hit a total of 180,000 copies, cumulative. European publishers are known to have empathized with the book saying “the social oppression that women have to endure and their human rights are globally common issues,” according to the Korean publisher.

They advocated for the female writers who stood up and the writers’ works again aroused the readers’ attention.

Feminist novels and accusations of sexual harassment in the literary circle

Young Korean women novelists prompted the wave of Korean feminism, which in turn motivated female novelists. The copyright of <About Daughter (Minumsa)>, written by Kim Hye-Jin and published in September 2017, was sold to Taiwan, Vietnam, Japan, and the Czech Republic. The novel tells a story of a mother who used to live by herself working as a caregiver, and now, all of a sudden has to live with her lesbian daughter and her girlfriend. <To Hyun-Nam Oppa (Dasan Bookstore)> came out in November 2017 as an editorial collection written by seven female novelists including Cho Nam-Joo and Choi Eun-Young under the theme of “feminist novel.” Cho Nam-Joo, the author of the headliner “To Hyun-Nam Oppa”, calmly reveals the hierarchic relationship and unpleasant discomfort between the main character and her boyfriend Hyun-Nam Oppa (Oppa is used by females to call an older brother or a close male older than her) whom she has dated for 10 years. To tell the story, the writer employs a letter she writes to her lover to refuse his marriage proposal. Novels that are considered to be influenced by or have had an impact on feminism are as follows: <Belatedly to My Sister (Changbi, 2019)> by Choi Jin-Young, a head-on account of the real feelings and the situation experienced by a victim of sexual crime who spent her childhood in the 1980s and 1990s, <Warm-hearted Community Club (Munhakdongne, 2019)> by Yoon Yi-Hyung, featuring 11 short stories on the topics that include misogyny, sexual violence, and queerness, <Snow, Man, and Snowman (Munhakdongne, 2019)> by Im Sol-Ah, which highlights sexual misconduct widespread in the literary circle and dissonances between victims of sexual crime while they try to build solidarity, and <Port Love (Minumsa, 2019)> by Kim Se-Hee, a long novel that describes homosexuality and the kpop fanfiction culture among teenage girls. <Putting a Bandage (Jakka Jungsin, 2020)> by Yoon Yi-Hyung is a novella that depicts the connections and tensions that exist in a women’s community.

<Belatedly to My Sister>. <Snow, Man, and Snowman>, <Port Love>

The works of these female writers are also related to the #MeToo (hashtag) movement (#sexual_violence_in_the_literary_circle) that took place on Twitter in mid-October 2016 and multiple sexual harassment scandals in the literary circle. The campaign essentially became an important part of the #MeToo movement in the community as some respectable male poets, novelists, and critics were accused of sexually harassing female literary rookies and apprentices. The entire society started to speak about the horrors and threats women have felt, and Korean female artists fought fiercely risking everything they had – the fight also continued in courtrooms. The struggles by women writers and apprentices pointed to the reality that the literary world is based on a highly discriminatory and male-centered structure, not an equal community for male and female artists. The newly-unveiled truth was a substantial shock for Korean women in their 20s and 30s who read a lot and love literature. They advocated for the female writers who stood up and the writers’ works again aroused the readers’ attention.

<Breaking the Literature>, <Awfully Literary Taste>

Critical debate on literature and feminism has also gained momentum. <Breaking the Literature (Minumsa, 2018)>, <Awfully Literary Taste (May Book, 2019)>, and other critical essays of women writers are of great significance as they reassess the entire Korean literature through a “feminist prism.”

Korean women are now essayists themselves, actively participating as readers.

Works actively produced by Korean female writers

In science fiction (sci-fi), short- and mid-length novels by female writers have recently become very popular. In 2018, <Sci-Fi Short Story Collection (Onuju)> was published, becoming the first Sci-fi editorial collection to be written by women artists. Another book that gained huge popularity was <If We Cannot Move at the Speed of Light (Hubble, 2018)> by Kim Cho-Yeop, who became well-known also from her master’s degree in biochemistry. Kim Bo-Young’s novels are also trendy and she is known to be consulted in the science section of the scenario for the film <Snowpiercer (2013)> produced by Bong Joon-Ho, a renowned Korean director. Copyrights of her works have been sold to HarperCollins, the largest publishing group in the USA, among which the English translation of <I’m Waiting for You (Toonism, 2015)> will be released in 2021. Also in November 2019, a dedicated sci-fi mook <SF Today (Arte)> was published, featuring works of Jung So-Yeon, Jeon Hye-Jin, Jung Bo-Ra, Lee Da-Hye, Dunah, and Kim Cho-Yeop. Their sci-fi stories are not only about artificial intelligence (AI), the Anthropocene, and climate change but also about the consciousness of feminism. This enables them to provoke thoughts via imaginative stories of the less privileged and the minority of society.

<Sci-Fi Short Story Collection>, <The autobiography of Death>, <To Write as a Woman: Lover, Patient, and You>

In poetry, Kim Hye-Soon received Asia’s first Griffin Poetry Prize in 2019, the world’s most prestigious award, for her anthology <The autobiography of Death (Munhak Silhumsil, 2016)>. In 2002, the poet published an essay on poetry <To Write as a Woman: Lover, Patient, Poet, and You (Munhakdongne, 2002)> which explains what “female writing” is. She illustrates how hard it is for women to speak with their own voices in the most patriarchal society. Also featured in this book is Bari-degi (meaning “abandoned child”. also called as “Bari”), Korean mythology in which she used the image of a female priest. She did so to emphasize the worst impression of misogyny that it makes women hate themselves. Even though she was abandoned as a child, Bari-degi does not fall for self-hate and strives to confront her own emotions. Kim says, “Dear poets, particularly women poets, we have no tradition, predecessor, or bible. For us, the bible is our body. So, try to read your body than doing something else.” (From <To Write as a Woman: Lover, Patient, Poet, and You>, 2002, p. 232)

<Elegant and Exciting Women’s Football>, <Resigning as Daughter-In-Law>, <Grass>

Korean women are now essayists themselves, actively participating as readers. Rather than choosing the topic of having a beautiful body, the essays of female writers who develop physical strength through work-outs or who struggle to manage their relationship with their mother-in-law are resonating more with the readers. <Elegant and Exciting Women’s Football (Minumsa, 2018)>, <Women Who Work Out (Homil Books, 2019)>, <No More Work-out Procrastination (Dasan bookstore, 2019)>, and <Physical strength: the No.1 Quality for Women (Memento, 2019)> are some of the good examples. <Myeoneuragi (Gyul Press, 2018)>, a comic series by Soo Shin-Ji was a big hit with the story of a just-got-married woman and her struggles as she lives as a daughter-in-law. <Resigning as Daughter-In-Law (Saiplanet, 2018)> features a story of the author herself abruptly “resigning” from her role as the first daughter-in-law (wife of the eldest son) in the family while being a mother of two children in the 23rd year of marriage.

Other books well received in both home and abroad were about human rights activists who testified as one of the “comfort women,” a euphemism for women who were forced into the Japanese military-run brothels during World War II. <Grass (Bori, 2017)>, a graphic novel written and illustrated by Kim Keum-Suk, is a harrowing account of Granny Lee Ok-Sun’s record as she lived as a “comfort woman.” It was given a Special Judges’ Award by the progressive French daily L’Humanité. Translated from Korean by Janet Hong, the book is now available in English (published by Drawn and Quarterly) in the USA, Canada, and the U.K.

Written by Lee You-Jin (Hankyoreh Books Team Staff Writer)