Although Korea is an economic tiger and today fiercely mobilizes its culture into all parts of the world, its history and cultural perception has limited its advancement of topics such as race, gender, and sexuality from developing away from more traditional standpoints. Part of this is due to a lack of active voices and inquisitive exploration into both the individual comprehension and political atmosphere that would allow for the encouragement of such conversations. Particularly, the topic of gender roles and inequality—both historical and current—remains largely untouched in Korea. However, an ensemble of brave and necessary voices has paved the way to reconcile such difficult topics, breaking down barriers and contributing unique narratives that encourage feministic values through literature.

Comfort Woman and Fox Girl by Nora Okja Keller

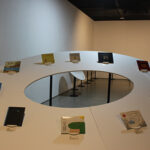

Comfort Woman and Fox Girl, both by Nora Okja Keller, are the first two books in an anticipated trilogy that explores the sexualization of Korean women to the Japanese army in the midst of World War II. It emphasizes the mistreatment of women in historical times that continues to be emphasized in Korean society today. A literary perspective depicts the taboo realities—albeit somewhat fantasized—of prostitution and gender roles that fiercely define women and their status. Comfort Woman, narrated by the voices of Akiko, a Korean refugee, and her daughter, Beccah, a product of a forced marriage to a white missionary, brings a sorrowful encounter and reconciliation of tragic memories of sexual slavery to a mother who is still suffering from the trauma and a daughter who struggles to understand her mother’s secret pains. The title Fox Girl originates from a Korean folktale about a fox that transforms into a girl. In this thematic exploration of change and self-awareness, the second novel follows the life of a teenage girl living in America Town—a place for the abandoned products of World War II. All mixed race, the people of America Town live in poverty, desperately searching for a way out through prostitution, which is the only way to make their way up the social ladder in a society that condemns those who are impure in blood. Through her novels, Keller fashions two beautiful stories that tell the traumatic tales of the historically lined anguish of women under male domination by the works of a lyrical spin. She exposes the realities of Korean women sold into sexual slavery, both bringing to light a usually undermined historical truth and encouraging conversations of feminist values and how these ideals have carried into Korean society today.

If I Had Your Face by Frances Cha

For a progressive society that values loving oneself and finding beauty in the ordinary, plastic surgery seems to redefine the standards of beauty as well as the happiness and success that seems to rest on physical appearance. As women all over the world are taught to admire their bodies and faces, and lift other women up, Korea tends to encourage the emphasis on face reconstruction to fit the stereotypical Asian beauty standard. If I Had Your Face by Frances Cha fights to break this stereotype, depicting the realities of everyday life and the unfortunate consequences and benefits that follow a life pursuing displaced value on outer appearance. The novel follows the lives of four very distinct women facing the challenges of their occupations, social lives, and families. Kyuri is a beautiful woman who is able to successfully cater to the interests of wealthy businessmen in a salon room through her plastic surgery. Her roommate, Miho, struggles with a troubling past while attending an art school in New York, as well as with a complex relationship with her boyfriend. Their mute neighbor Ara is a hairstylist dwelling in her celebrity fantasies and, a floor below, Wonna worries about securing a stable future for her family to avoid the trials of her own life growing up. In a society motivated by wealth, beauty, and social standing, the four women struggle to fight for their own individualities and strength in self both independently and through their friendships. The novel sheds light on the sometimes overlooked malicious and competitive atmosphere of Korean society, one in which women are expected to conform to a specific appearance and behavior in order to be socially accepted. The specific intersectionalities of beauty, social standing, and relationships offer an inside look into the realistic struggles of everyday life that many Korean women face today. Cha deliberately avoids a finished and happy ending in order to portray a more authentic image of the continuing battles of women within Korean ideals of conformity. The direct impact of this conclusion is a creation of concern: concern that properly necessitates the recognition of a lack of equality and fights for an atmosphere of safety and comfort of just being a woman. No one should fear the consequences of not looking a certain way or adhering to a code of conduct. If I Had Your Face recognizes the possibility of achieving success through more than one means.

Who Ate Up All the Shingah? by Park Wan-Suh

Park Wan-Suh, who lived from 1931 to 2011, experienced some of the most prominent events of Korean historical tragedy and change. Because of this time frame, she was able to translate her experiences into written work, dwelling on her own emotions and understanding of Korean cultural and social changes throughout the Japanese control over Korea and World War II. Her novel, Who Ate Up All the Shinga, is told in an autobiographical light and weaves the perspectives of a mother and her daughter centered around their hometown, Bakjeokgol.

Although the mother views Bakjeokgol with a negative light, representative of her struggles and a lack of modernity and education, the daughter perceives her childhood home as a place to relish. As the daughter grows older, she struggles to reconcile the feeling of leaving her childhood home as one of sorrow, but also as an opportunity to pursue a successful future. Told within the underlying trials of Korean society and advancement into a modern age, Who Ate Up All the Shinga explores the strained but loving bond between a mother and her daughter struggling to adapt within new environments constrained by societal and personal ideals in their own ways. Park deliberately works to capture a narrative retold in a feminine light, recounting historical events and consequences that are usually interpreted through the voices of men. By taking back authority over these tales and narrating through the distinguished sensibility and emotions of a female voice, the novel depicts the realities of both historical and current struggles of Korean women through a discovery of self in a changing world. The book encourages women to narrate their own stories within a timeline that suits their own values. Feminism fights for motivating women to simply be women, without the restraints put on by a patriarchal world that offers limited pursuits.

Kim Ji Young, Born in 1982 by Cho Nam Joo

Kim Jiyoung, Born in 1982, by Cho Nam-Joo, took Korea by storm through a controversial but riveting tale that challenged Korean societal norms. Written in a deliberately detached voice, the novel narrates the story of a very ordinary woman living in Korea. The unusual ordinariness of the story is emphatic through its underlying message—that there exists in every aspect of the protagonist’s life a battle to overcome male misogyny. Even from birth, Kim Jiyoung faces the burdens of a society that puts its focus on men and forces gender roles upon women who then either have limited options in life, or are given success only through a dependence on men. By advancing the ordinariness of her life, it demonstrates that an “ordinary” life is stereotyped with assumptions about women through their roles in family, society, and occupation. The novel sparked much needed debate about the obvious sexism in Korea and the underlying pressures that force women to adhere to societal standards. The protagonist exemplifies a life that directly addresses the ability, and sometimes lack of ability, of women to stand up for equality. However, through an acknowledgement of a current limit on ability, it thus draws attention to the mobilization of change and direction toward women’s rights.

Today, gender inequality in Korea is ranked one of the highest in the world, coercing and pressuring women to be bound by gendered stereotypes that inhibit their freedom and individuality. Although much of these struggles are centralized through systemic concerns that will take years of intentional change and cultural advancement to be fully breached, these Korean authors make important and influential landmarks in creating conversation toward feminism through their literature.